Totem of Healing: Interview with Tlingit Artist Took Gregory

Took Raymond Gregory is a Tlingit artist, he was born in Juneau, Alaska, and spent his summers in the traditional territory of his Tlingit people in Angoon, Alaska. These times forged his connections to the history and culture of his people. As an adult, his art has explored and expressed those connections, a journey he continues with today. He also is a traditional Tlingit singer and dancer.

The Tlingit people have been living in southeast Alaska for thousands of years, with a long history of connection to areas in what is now Alaska, British Columbia and southern Yukon in Canada. Today, Gregory says, the “connections are getting stronger”. Cultural celebrations and the teaching of tribal languages and art programs aid in keeping the Tlingit people recognized in a modern world.

Gregory’s art focuses on keeping that heritage alive. He was in his early twenties before his artistic career began. In the Tlingit culture, a person’s matrilineal uncle is part of helping raise them. Gregory went to his Uncle Donald, his mother’s brother, and asked if he would teach him how to draw formline. His uncle also taught him engraving. As he grew more proficient at these, his uncle gifted him with a jeweler’s block and engraving tools.

As Gregory explored his art, more opportunity presented themselves to expand it. The Goldbelt Heritage Foundation had received a grant that would offer apprenticeships to Tlingit artists wishing to learn from a master carver. The goal was the creation of a healing totem pole to be placed in Savikko Park in Juneau. The totem would recognize a tragedy which took place in the city of Douglas.

Douglas was the site of a small village belonging to a Tlingit group known as the Taku Kwaan. The Taku migrated between this village and their summer fishing village. In 1962, Tlingit people, desiring to receive a loan for a powered boat and a harbor for their village in Douglas were in the process of making a deal between the city, as long as they moved their village further away from the land it occupied. The city of Douglas would soon after setting fire to the Taku village while most of the people were out at fishing camps they would work and live for the summer. The city of Douglas burned homes and belongings, even though the places did not belong to the city. It created a great rift between the Taku Tlingit and the city, one in need of both recognition and healing. This was the purpose the Goldbelt Institute sought to serve with this totem pole carving.

Gregory applied for one of the apprenticeships and was accepted into the program after being interviewed by a panel of Tlingit people from Goldbelt Heritage Foundation. Along with the carving skills it offered, there was also the opportunity to teach local school children how to carve traditional items such as fishing lures and canoes. He spent the summer teaching in youth camps and found he enjoyed being a teacher. They made red cedar rope as well. To his satisfaction, a couple of the high school students really took to carving and ended up becoming apprentices for the same organization and carved smaller house posts for the school that housed the larger 40-foot totem pole as a showing of gratitude.

The long task of carving the pole reinforced for him the Tlingit beliefs about the importance of such totems. They were not to be taken lightly, he says, for they represented “who you were and recognized your opposite tribes to keep relationships going.” This particular totem held even more significance due to its focus. As Gregory puts it, the “focus was to heal, to recognize and to reclaim our traditional spaces.” For him, this recognition was important. He grew up only fifteen miles away from Douglas but was twenty-six before he heard the story of the fire. Future generations would know what had happened thanks to the totem pole he helped to create.

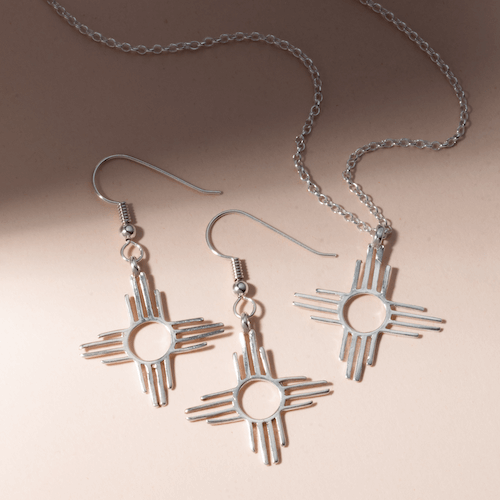

Recently Gregory is working for Rico Worl apprenticing under him for metal engraving, formline, and other styles of Tlingit art, it’s in a space where he plans to learn even more about his art and connect with different styles of applying formline or modern Tlingit art to his practice.