The Art of Charles Loloma

Art is a fluid medium, changing and evolving over time from the inspiration of those engaged in it. Even a traditional art form such as Native American jewelry has felt the effects of evolution on its styles and materials. One artist who pushed the boundaries of tradition and brought evolution to the world of Native American jewelry and art was Charles Loloma. Loloma’s art was unique, reflecting not only his Hopi culture but his world travels and life experience.

Many consider him “the most influential Native American jeweler of the twentieth century” because of this willingness to expand traditional styles with new ideas and new materials. As Wheelwright Museum curator Cheri Falkenstien-Doyle puts it, Loloma was “able to pull information from so many sources and use it.” His unique approach to his art gained him world renown. Lady Bird Johnson commissioned him to create pieces for President Johnson to give as gifts for such dignitaries as the Queen of Denmark.

Born in the Hopi community of Hotevilla in 1921, Charles Loloma was a man of diverse interests. He was a Hopi Snake priest, a world traveler, a potter, a weaver and a self-taught silversmith. Loloma served with the US Army in the Aleutian Islands during World War II, venturing on to New York after the war. There he attended Alfred University where he studied ceramics at the School for American Craftsmen.

Charles Loloma 1921 – 1991

His willingness to diverge from the traditional styles of his culture were evident even then. According to Mark Bahti, the son of Charles’ good friend Tom Bahti, Loloma created ceramics in the 1950s and 1960s that were “Hopi interpretations of Egyptian figures, with Hopi hairstyles, executed with remarkable grace.” This blending of traditions would be a hallmark of Loloma’s work throughout his life.

It would also lead to the judgment by some that Loloma’s work was not “Indian enough“. This was a commentary that other artists who were attempting to push the boundaries of what would be considered Native American art would face as well. Loloma found his work rejected from noted competitions because of this feeling that it did not meet the style of true Native American jewelry. Despite the fame his work would bring him, this rejection hurt. As Loloma put it, “They didn’t realize I was interpreting the depths of Indian vision.” It would become a frustration which, thankfully, did not deter him from exploring the boundaries of his art. Over time, Loloma’s work would receive the credit it deserved even among traditionalists.

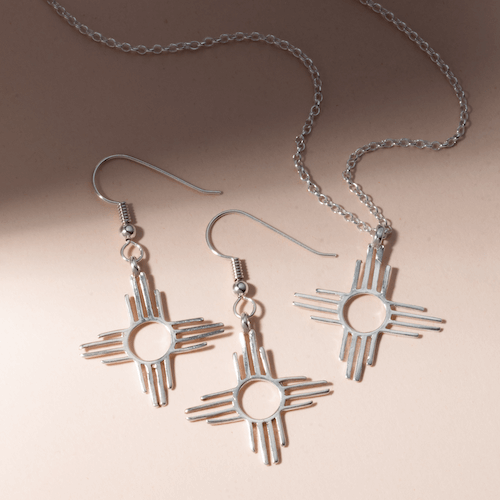

His work evolved over the years of his career. Loloma included a variety of colors and stones in inlay jewelry, using the geometric designs from Hopi culture combined with additions of coral, wood, turquoise and lapis lazuli. One particular element, which Loloma himself believed was his greatest contribution to the art of jewelry, was to include what he termed “inner gems“. These were stones hidden on the inside of the piece, unseen when the piece was worn. To Loloma, they were to be a reflection of the inner beauty of the wearer. Many times these gems were more valuable than the ones on the outside of the piece.

In spite of the fact that he straddled two worlds in regards to his art, Loloma remained deeply involved in the world of the Hopi. Though he travelled all over, he came home to the Hopi mesas. His pieces included interpretations of his Badger Clan symbol, of serpents and lizards and corn maidens. Those who knew him say he did not speak about the Hopi religion, yet his work reflects Hopi imagery and the landscape and geography of the Hopi mesas. As Loloma put it, “All Hopis are artists. We are raised on it – theater, songs, making instruments.” He remained a Hopi spiritual leader and ceremonial clown, continuing to live at the Hopi Third Mesa even as he traveled the world making connections with his art.

Charles Loloma Hallmark

An auto accident in 1986 caused Charles Loloma’s health to decline. In spite of a brief recovery during his time at the Barrows Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Arizona, Loloma’s health again declined and he passed away in Phoenix at the age of sixty-nine. He left behind an artistic legacy that defies tradition even as it embraces it. The work he created reveals the depths of Loloma’s willingness to search the world over for inspiration along with his desire to include all the wonderful things he found in both his own culture and those he explored on his travels. To Charles Loloma, the earth itself was his palette. In a video from 1974 which discussed his art, Loloma put it best when he said, “I wish to create a relationship between the earth and myself.” When one looks at the legacy he left behind, it is clear he did just that.

Charles Loloma, 1980 Photograph courtesy of Georgia Loloma

Resources:

http://www.ganoksin.com/borisat/nenam/charles-loloma.htm

http://craftcouncil.org/post/charles-loloma-man-many-talents

http://www.temple.edu/crafts/metalsdirectorypage/biographies/b105.html

http://marthastruever.com/charles-loloma

http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/past-exhibitions/totems-to-turquoise/master-artists/charles-loloma

http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20071246,00.html