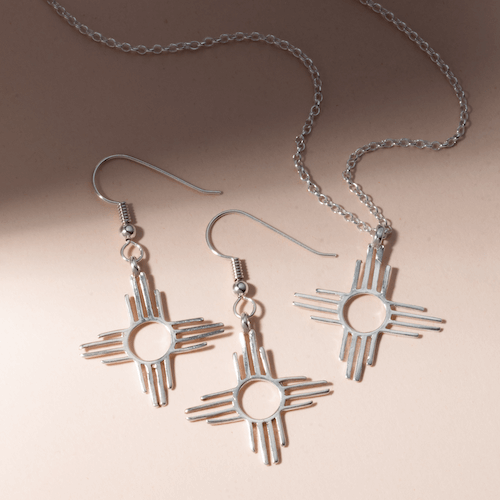

The Naja

We celebrate the Naja for the legacy it holds of war, survival, and beauty in the Southwest.

The Naja design is a reminder of the Diné (Navajo) people’s resilience in the face of unimaginable adversity. It is a symbol of creating something beautiful out of despair, of rising from the ashes, of fertility and new life.

“Diné learned silversmithing from people to the south,” says Paulo Dineclah, a Diné elder. “They picked up silver coinage from them and melted it down to make Concho belts. It is said we wear turquoise jewelry, diyiin dineh, to acknowledge and honor land, people, and show respectfulness to a good life.”

The Naja, which is the crescent pendant at the center of the Navajo squash blossom necklace, has roots in the Goddess-based religions of Phoenicia, Greece, Crete and Rome where it could have represented a pomegranate and used as a fertility symbol. However, it was the Moors – who dominated Spain for eight centuries – who adopted what would become known as a “Naja” on their horses’ bridles to protect the animal and its rider against “the evil eye”. In the 16th century, the Spanish arrived in the New World in search of gold, executing their conquest upon ornamented Andalusian horses and introducing the Moorish bridle design to the Diné and other first inhabitants.

“The Dine' people are very articulate people especially in art,” says Ceria Hogue, a Diné elder and matriarch we spoke to about the significance of the design in her culture. “Since the Diné planted vegetables and one of them was squash, squash has blossoms. Also, as mentioned, there were the silversmiths and the

horses. The Diné people adopted the horses, horses have horseshoes. So all in all, maybe they designed their jewelry after something of significance to the Diné people.”

While Diné don’t consider the Naja to have any spiritual or symbolic significance in their culture and religion, they have always been held in high esteem as a form of wealth and bravery, proudly worn by men and women. First contact with the Spanish, who were adorned and armed in never-before-seen metals and riding atop strange four-legged beasts, was of course a moment that would forever affect the lives and culture of the Indigenous peoples of land. To survive, the Diné became fierce warriors and to return from war or raiding parties with Spanish Najas was most likely a way of counting coup on their enemy.

“The original idea of the Naja could have come from our beliefs in harmony that we live by as Diné people,” says Carmalie Denetclaw, who is also a Diné elder and matriarch. “Our people always believed that the most sacred center of our existence centers around the hogan.”

It wasn’t until the 19th century that the Diné began to integrate silversmithing into their lives and culture, a practice that was also imported from Spain. The ability to work in silver, leather and other metals allowed the Diné to move their culture from a warrior society to that of a merchant society. The Long Walk of 1864, a forced 300 mile relocation and detainment of all Diné people by the United States, was also a key moment in the necessary adaptation from a nomadic to more settled existence.

Upon the Diné’s return from their four-year detainment at the Bosque Redondo internment camp, life was forever altered. Where prestige and wealth used to come from raiding, it now came from herding and trading. Silverworking became a very important part of this transition. At this time the squash blossom necklace,

most famous for its inclusion of the Naja pendant, became popular. The squash blossoms are represented as having long petals at the brink of opening,

connected to a spherical bulb at the base of the blossom. While the squash plant represented life and sustenance to the Diné, originally the flower pendant represented the pomegranates of Andalusia where a variation of this design can be found in the motifs of Granada, Spain.

“My son, Andrew, suggested that to be in perfect balance with life, we follow a path that leads out to the East (from the hogan) with a circle around us, and from the East everything leads to ‘hozhon’,” says Carmalite. “The opening in the Naja could represent this belief to the original Diné Naja artist...The Naja on the squash blossom should be symbolic to the path of goodness.”

Story & photos by Ungelbah Dávila-Shivers.

Ungelbah (Ungie) is an award winning Diné writer & photographer, and IAIA alumnus.

@udavilaphotography